In the year of the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, two American films were produced that would retain significance more than 40 years later to our present day. One of those films, the adaptation of Bob Woodward’s and Carl Bernstein’s book, All the President’s Men,1 is an affirmation that the principles of American journalism remain relevant today as Congress impeaches another President. The expectation that reporters, such as Woodward and Bernstein, should be independent of authorities exerting pressure on them as they investigated Nixon’s efforts to cover up the Watergate break-in, stands as a testament to the ideals of American journalism. The other film, Paddy Chayefski’s Network,2 intended to be a satire of the television news business in 1976, ironically became prescient of the direction network news would travel since the film premiered and has been subsequently reappraised by many film critics. Far from representing the triumph of an independent news organization, the film depicts the corporate and public pressure placed upon the organization, resulting in an absurd (for that time) news program that would eventually conclude with the murder of the news anchor and the death of news as an independent ideal —or as Pauline Kael would put it in her 1976 column reviewing Network, the symbolic character representing Edward R. Murrow, “loses his fight to keep the news independent.”3 Although the film is fiction, many of Network’snews depictions have become normal today in the world of American cable news programs, such as Fox News Channel, CNN and MSNBC.

The fact that both films would seem unusually relevant today would appear to be coincidental, but the historical narrative is expected to be told in linear fashion and one can trace the origins of both stories from around the beginning of the 20th century. Furthermore, from the films’ premiers, one can equally identify the influences that lead directly to the impact of our current reality show President. In this essay I will examine the rise of the American public relations industry, specifically the influence of Edward Bernays, and the emergence and importance of an objective and independent press. Following that historical perspective, I will demonstrate how the films reflect our current political media crisis by examining media developments from the seventies to the present time. First, however, I will revisit the 1976 films, describing a world and a time that was both idealistic and cynical. My intent is to show how these popular journalistic films of the same era came to represent a linchpin between an optimistic age of growing American influence in the world, and our current political situation— as many question the existence of truth and facts, and as Fox News has become the President’s network, trading in disinformation and conspiracy theories.4,5

Competing Authorities

By all appearances All the President’s Men and Network were separate but equal perspectives on the state of journalism in the seventies. Each film won four academy awards.6 Both won respective awards for their screenplays: William Goldman for his adaptation of Woodward and Bernstein’s book and Paddy Chayefski, who wrote the original screenplay for Network. Alan J. Pakula, the Oscar nominated director of To Kill a Mockingbird helmed All the President’s Men and Sidney Lumet, whose previous film had been Dog Day Afternoon, directed Network. Actors in both films were nominated and received Academy Awards.

The stories and how they were told were quite different. All the President’s Men is a detective tale, tracing Woodward and Bernstein’s trek across Washington, tracking down clues into the burglary of the Watergate Hotel, following the money as “Deep Throat” advised, and ultimately helping to extinguish Nixon’s presidency. Network is an original story about a television news anchor going insane and subsequently being fatally exploited by USB network corporate owners in the name of higher ratings, which equals profits.

Roger Ebert, film critic for the Chicago Sun Times gave the Woodward and Bernstein tale nearly a perfect score but griped (ironically) about its authenticity. “[The film] is truer to the craft of journalism than to the art of storytelling. And that’s its problem.”7 Indeed, Ebert would say the film was so authentic it resembled a primer on the craft of investigative journalism. There is little, if any, subject matter about anything other than the professional pursuit of truth. No attention is paid to the reporter’s personal lives.

However, the mise en scene, apparently much to Ebert’s displeasure, is authentic. In fact, the film won the Academy Award for best art and production design.8 The exterior shots of Washington, D.C. in the seventies are contemporaneously real, of course, under certain lighting and perspectives, and much work and time was spent on the interiors; the space of the Washington Post newsroom is a fiberglass facsimile. The film’s newsroom image defined the look of journalism for a generation. 9 The long panels of fluorescent lights cast a bright and uniform illumination on the multitude of desks stacked with paper, typewriters and telephones. The space is large, prompting reporters to run through it and to communicate with others by shouting, as Post editor Ben Bradlee does, summoning the two reporters into his office by meshing their names, “Woodstein!”10

The overall impression inside the newsroom is one of clarity, despite the mess; the search for accuracy is embodied in Bradlee, who pushes the reporters to get facts, sources, and ultimately the story. “The truth” is meant to be a well-lit ideal. Contrast that image with “the search for truth” and those images, outside the newsroom, tend to be overcast or at night in gloomy houses, apartments, parks, and especially the parking garage where Woodward meets with Deep Throat in the shadows. Similar observations are made by Jonathan Kirshner who, in turn, attributed them to Steven Soderbergh.11 These metaphors are potentially obvious to anyone watching the film although Kirshner reminds us All the President’s Men is the third of Pakula’s “paranoid trilogy.” Klute, The Parallax View, and this film are “draped in the signature darknes of cinematographer Gordon Willis, which contributes to that general tone.”12 The tone certainly contributes to the impression of the weight of the American government bearing down on the Post, threatening to destroy the paper’s credibility. Bradlee shares his anxiety with his persistent but frustrated reporters, “it'll sink the goddamn paper. Everyone says, "Get off it, Ben", and I come on very sage and I say, ‘Well, you'll see, you wait till this bottoms out.’ But the truth is, I can't figure out what we've got.”13 Only a reporter’s integrity and independence can induce the courage to confront the government’s authority. Yet Woodward and Bernstein are average men doing a job protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution. They live in small, no-frills apartments— but neither reporter spends much time there— and one can almost see a perpetual haze of cigarette smoke at Bernstein’s. Their lives are their work.

The same can be said of the character, Diana Christensen, played by Faye Dunaway in Network. Her work is her life at the expense of all else. Diana is the head of the Programming Department at the UBS network, tasked with creating new shows. In her role in this film she is a foil to the News Department, and more specifically to the Newsroom leader, Max Schumacher.

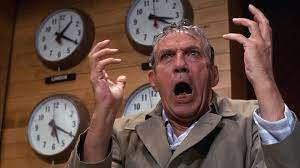

Schumacher had been a protégé of legendary newsman Edward R. Murrow, so Max represents the ideal of journalistic integrity. Diana seduces him and ultimately gains control of the news “product,” which she recreates with a psychic named Sybil The Soothsayer and a gossip segment with Miss Mata Hari. Her “star” is Howard Beale, the “Mad Prophet of the Airwaves,” a legitimate news anchor turned prophet. After announcing he would kill himself on live t.v.—and was fired— he was rehired after Diana took over and rebranded him. He becomes the man proclaiming the now-famous quote, “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!”14 Howard begins to believe God is speaking to him because, he reasons, he is the perfect messenger as he is on television.. That logic invites a later scene with a corporate executive who sets Beale straight on the power of corporations.

Meanwhile, Max is becoming irrelevant both professionally and personally and becomes involved with Diana, as she is the metaphor for the powers that are assaulting independent news. In their relationship, however, Diana is revealed to be a distracted sexual partner who loves only her work. The two are obviously from different generations, which is important. Max says of Diana, “she’s television generation she learned life from bugs bunny. The only reality she knows is what comes to her over the tv set.”15 She develops a reality show with a terrorist organization, which is a crime, but skirts the problematic association by claiming it is news. She tells the terrorist organization’s representative, “we're getting around the FBI by doing the show in collaboration with the News division! We're standing on the First Amendment, Freedom of the Press, and the right to protect our sources.”16 Essentially, she usurps Max’s power. Her efforts result in a spike in ratings, meaning the USB Corporation makes a lot of money.

Despite her role as the villain of the film in 1976, over the years some critics have reappraised her character. BBC critic Nicholas Barber writes, “if several of the characters and concepts in Network have made the journey from ‘outrageous’ to ‘ordinary’ over the past 40 years, Diana has gone further: she now looks a lot like the film’s heroine.”17Part of the reason she is seen differently over time is that what she represents has been seen differently over time. What Diana did in 1976 was seen in a more idealistic time as an intrusion on a sacrosanct occupation. She is a program developer and a promoter. Her job is to get people to watch the network, so in that sense she is a marketer. Although her title is not Public Relations, essentially her function is. She is especially the representative of the UBS Corporation in the newsroom and her mandate is profit through ratings and shares. Over the years the American perception of Public Relations has changed considerably over the last century (which will be explored below). Today Public Relations is considered by many to be an admirable profession in our increasingly capitalistic society, but that perception depends on the industry’s ethics.18 Seen from 1976 the film’s narrative shows how the imposition of corporate efforts to put profits above news quality had been a growing concern in the relatively young television news industry. Today there is nothing but corporate control in the television news industry. The film ends with the corporation murdering Howard Beale on the air, the narrator’s voice remarking, “This was the story of Howard Beale, the first known instance of a man that was killed because he had lousy ratings.”19

Film critic Pauline Kael was ambivalent about the film in her 1976 review in The New Yorker, praising all the actors— many of whom she had long been observing— but taking issue with what she interpreted as writer Paddy Chayefsky’s penchant for rants in his body of work. Of Beale she said, “he’s like a village crazy bellowing at you: blacks are taking over, revolutionaries are taking over, women are taking over.”20 Yet Beale’s speech in that scene perfectly reflects the 70’s angry and frustrated human cry over urban blight and economic stagnation. “It’s a depression. Everybody’s out of work or scared of losing their job. A dollar buys a nickel’s worth. Banks are going bust. Shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter. Punks are running wild in the streets and there’s no one anywhere who seems to know what to do and there’s no end to it!”21 Kael describes the film as a farce because of its obvious (in its day) heightened reality and absurd plot twists. However, Chayefsky, a playwright, employed a theatricality to his language, veering into didacticism, that would not be found in a film like All the President’s Men. Interestingly, Chayefski apparently tried to make the language less theatrical.22 Because Kael knew the rants were really Chayefsky speaking through the characters, she apparently felt alienated not being able to follow the story without thinking of Chayefsky, particularly because practically every character had a ranting moment.23 Clearly, though, Network is a biting satire. It is much more intelligent than simple exaggeration and physical comedy.

In terms of the look of the film, Lumet and cinematographer, Owen Roizman, came up with what Lumet had envisioned as a progressive approach to lighting. The film would begin with naturalistic light and would progress with more artificial light, until the end, when the light would be like that of a commercial.24 Again, that strategy represents the journey from the real world to that of the corporate perception of profit. What is striking is how often a scene has many points of light on darkness. For example, there are the banker green glass table lamps during Beale’s reprimand scene. The corporate CEO shuts the curtain before he begins his rant, which makes the light and darkness more contrasting. The same effect is achieved after Beale’s “Mad as Hell” speech when Max looks out the window and sees various people yelling from their open, lighted windows contrasting against the black night during a rainstorm. In the studio scenes the studio is black but various items are lit, such as monitors, and parts of the set.25 There are many scenes in offices where the light seems bright and natural, streaming into windows of a high-rise, belying the ominous and absurd conversations in the rooms. Yet despite the attention paid to light, as in All the President’s Men, the mise en scene in Network is dark, like the subject matter of both films: governmental abuse and corporate profit. As Kirshner observes, “that profit motive legitimizes all kinds of crimes, and perhaps worse, all kinds of transgressions.”26

The cities of New York in Network, and Washington D.C. in All the President’s Men, are primary characters in the films and they also represent the respective centers of power—the dark authorities the protagonists are battling. The Washington Post had the White House. The UBS newsroom had its capitalistic corporate managers. Nixon had broken the law but nevertheless had great power in the office of the Presidency. In the cover-up of the burglary at the Watergate hotel Nixon had abused his power. Much of his administration would be given prison time after the facts were known. The point is that the facts became known thanks to the diligence of Post reporters, Woodward and Bernstein. Nevertheless, all U.S. Presidents have grappled with power in their own way, but the founders of the American nation were prescient enough to understand that freedom and independence from other powers was dependent on knowledge, specifically the free flow of information. Not only does the First Amendment guarantee a right to free speech, it also guarantees a free press, a mechanism by which speech and knowledge — or “truth” — can be disseminated. A free press acts as a check on power. In a nation wary of monarchs or other potential authoritarian impulses, a free press is democracy’s best friend. In the U.S. the rich and influential will always have a measure of power, but the majority of “we the people” essentially depend upon each other to hold up our end by being informed before voting or forming opinions and taking stands. That is an ideal, of course. Yet America is founded on an idea, unlike its parent nations founded on hereditary rights.

Ben Bradlee in All the President’s Men felt the pressure as the investigation moved closer to Nixon, “We're about to accuse Haldeman, who only happens to be the second most important man in this country, of conducting a criminal conspiracy from inside the White House. It would be nice if we were right.”27 Given our understanding of the nature of power, we understand even the press can abuse it and has done so frequently in American history. There are many stories about William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer and their Yellow Journalism.28 To help counter these abuses, the Code of Ethics for journalists were first drawn up in 1926.29 The spirit of that code, with a few changes, remains today the expectation of how professional journalists honor the responsibility they have undertaken in a free society. Today the primary responsibilities are to minimize harm, to be transparent, to be independent, and above all, to seek out the truth and report it. Woodward, Bernstein, Bradlee and the other Washington Post journalists honored the code in All the President’s Men, putting their credibility and public trust on the line for the truth. As Bradlee interpreted the stakes, “We're under a lot of pressure, you know, and you put us there. Nothing's riding on this except the First Amendment to the Constitution, freedom of the press, and maybe the future of the country. Not that any of that matters.”30 In one interpretation, given the importance the nation’s founders placed on a free press, what the Post did by exposing the Watergate story, was patriotic. The American press put an end to abusive power by following Deep Throat’s advice: “Follow the money.”31

Not everyone saw it that way. Nixon did not, nor did one of his aides, a young Roger Ailes. They both agreed had Nixon had a news channel sympathetic to him, he would not have been impeached. Ailes would go on to create The Fox News Channel. 32

Foucault said, “power is everywhere,”33 He coined the term “power/knowledge” to mean that power comes from the things we accept as knowledge. However, because those things are recognized as created by us and so are subject to change by us, the inference is that truth is created by us. As he said, “truth is a thing of this world. It is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint.”34 We create truth and we subsequently enforce it. Truth can change then, by discourse or confrontation. Politically, Nixon was claiming truth and the Post was claiming truth, but the Post won because Nixon DID do all the things of which he was accused because evidence was found. So, if the evidence existed but it was not found and Nixon declared his innocence, would he have been truthful? Nixon’s assumption is that if he had a sympathetic news network, his message would have equally countered the media’s message. Again, the assumption is that, all things being equal, if no evidence is found, no evidence exists. It is a remarkably cynical way of looking at things—although it is the way science looks at things— but it is not the way journalism looks at things. To seek out the truth and report it suggests truth exists regardless of whether it is known.

In that spirit a moment must be taken to clarify the depiction of the power of journalists in All the President’s Men. They are depicted as working. On a personal level, within the limitations of the professional lens, they can be regarded as manipulative, abusing their own power with individuals being interviewed, and employing many strategies for obtaining information. As the film is structured the journalistic idealism is implied by the action of their investigation. So, because of the nature of film narrative, the story is being told selectively to reinforce the author’s image of representing the ideals of journalism. Need it be said that idealism is not reality? An idea is something to strive for, but not necessarily obtained. Concerning Watergate, Bennett argues “Most of the focus was on the misdeeds of Nixon and his associates, and little attention was paid to flaws in the secrecy and espionage systems that may have contributed to presidential abuses of power.”35 For journalists the larger issues are not necessarily within the scope of individual journalists to practically report within the limitations of a publication’s expectation of getting the story. Bradlee’s impatient character represents that fact. The power dynamic within the newsroom is, in reality—not ideally— part of the larger power dynamic that is distilled into the Watergate story. The film does not necessarily depict today’s journalism anymore than Network depicts today’s network news. They are only depictions created by authors that are authentic to the ideas the authors are promoting. However, they are powerful ideas, and as indicated by their success with critics and audiences, must ring true to many people. This constant power struggle between idealism and practical application has been waged in American minds since the American experiment began.

In simple American journalism terms, it comes down to writing a story before one has all the facts, because having all the facts is an ideal that may or may not be reached, but deadlines must be honored. Authorities may or may not be truthful, so journalists, ideally, do not take an authority’s word at face value because one should be independent of that authority. For Nixon to suggest a network should exist that is not independent of him, is to show, not only disrespect to the institution of the press, to a Constitutional guarantee, but to profoundly misunderstand the press’s function. The legitimate press, or what is today referred to as the mainstream press, is independent. A dependent press (what some observers today identify with Fox News Channel 36) is, by definition, a public relations exercise and will be regarded as such by the legitimate press. The powerful, that is, the rich and influential who can afford public relations services, are assuming what they create is in every way equivalent to “the people’s” voice, but it is equivalent to using power to silence that voice, or at the very least to drown it in a sea of voices. Metaphorically, truth is owned by who can scream the loudest.

Sidney Lumet, the director of Network, said for him, the corporate takeover of the news in the film, “was about corruption of the American spirit.”37 That was certainly the message Chayefsky intended to communicate. Chayefsky had worked in television several years before writing Network. In an earlier 1968 television pilot script that was never produced called The Imposters, Chayefsky could have been speaking to Diana Christensen when the protagonist rants:

"Because you’re not really in the entertainment business. You’re in the merchandising business. Your job is to assemble the largest body ofconsumers. You are, in short, shills for your sponsors. And television, the fountain of truth, is, in fact, being run for the benefit of a few giant corporations."38

So at least as early as 1968 the public was growing increasingly aware of corporate power in all things television, and the news was on television. Kirshner has an interesting observation:

Easily lost in a summary of seventies concerns about capitalism is the crucial theme of market encroachment. At bottom, anxiety about marketization is not a dissent rooted in economics; it is not a protest against profits, wealth or moneymaking more generally. It is instead the expression of a fundamental sociocultural concern. Where should the market rule? [Italics in original.] 39

That question is relevant today as education and prisons have been experimenting with market practices. In any event, as will be explained below, for good or ill, market dominance in the news industry is a fait accompli. Even the famously independent The Washington Post is owned by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Currently, Bloomberg news owner Michael Bloomberg, who is running for President has instructed his reporters not to cover his campaign nor his Democrat opponents in the primary. They may continue to cover Trump.40 His reporters are rightfully angry over the order and so is Trump. Independence from government authority is one thing, but reporters rarely have independence from their corporate owner. Bloomberg, a billionaire, is using his power as a media mogul to attack Trump, a counterpoint to Fox News, one might say. It is as if William Randolph Hearst is running for President as his fictional persona, Charles Foster Kane. Power is everywhere, but especially in the boardroom. Network’s philosophical climax comes via the network’s CEO as he pummels Beale with the “truth”. There are no countries; there are only corporations in a global economy.

The Road to ‘76

Dual perceptions of America — that of idealism and that of commerce— were applied to other cultures long before America, of course. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates compares two cities, one he calls healthy and the other he describes as luxurious. The healthy city produces only goods that people need to maintain the population. Socrates notes, however, that humans are rarely satisfied with only what they need and desire comfort and luxuries beyond the merely practical. The need for more leads to many of the miseries in civilized culture, such as war.41

Before there was an America there were two significant settlements in the land that have become symbolic for their history. Jamestown began as a colony for business. They brought slaves to the new world to work in the tobacco fields. Plymouth Rock was founded by the pilgrims, the Puritans, fleeing religious persecution from England.42 The ideas of the new land that would become America, as a place to find freedom of religion and as a place to make a fortune, have always been in the stitching of the new country.

By the time of the American revolution the press had been politically partisan but generally independent as enterprises. Only Benjamin Franklin answered for the Pennsylvania Gazette. He was one of the founding fathers of American journalism, establishing the idea that stories should consider more than one point of view and that truth should win out over anything else.43 The press was particularly partisan during the Civil War, prompting a reporter of the time to remark on facts. “The power of the press consists not in its logic or eloquence, but in its ability to manufacture facts, or to give coloring to facts that have occurred.”44 By the 1880s, however, the press started to turn on corporations and their predecessors, proprietorships, especially following the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, which had prohibited monopolies. Francis Thurber, a business lobbyist complained that “irresponsible journalists were fueling a wrongheaded legal crusade to criminalize the economically sound … and morally praiseworthy mergers and acquisitions that have been undertaken by…corporations.”45 Of course, by 1895, the Pulitzer and Hearst papers were at the peak of their Yellow Journalism war. While supporting the working class, who were their primary readership, they would help establish “muckrakers”—a pejorative term (via Teddy Roosevelt) that described investigative journalists who would go undercover and expose business or government abuses.46 A significant moment for the press and the rise of propaganda began in the build-up to the Spanish-American War. Reporters were fabricating Spanish atrocities (fake news) and the Hearst and Pulitzer papers were publishing them. When the USS Maine was sunk the papers blamed the Spanish, but no evidence was found to confirm Spanish involvement. Nevertheless, American soldiers, including Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, were sent to Cuba.47 It would be World War I, however, when government sponsored propaganda would be developed to a great degree. The British government printed posters to increase volunteers for the war. The Germans, subsequently, began to understand the value of propaganda.48 After the war, however, the U.S. would see the linking of propaganda with big business.

Edward Bernays was the nephew of Sigmund Freud. In 1928 when he wrote the book, Propaganda, he saw chaos on American streets.49 Immigrants continued to arrive, primarily from Europe, and there were various philosophies and different customs that came with the new citizens. This burgeoning population needed order. The very first words in Bernays book are, “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in a democratic society.”50 Bernays did not see propaganda as a bad thing. He imagined the possibilities of being able to exercise control over the masses so they would help support the 20th century economy and be expected to contribute to society in a positive way. He reasoned that there would be so many minds that would not know what to think that someone needed to guide them. Consistent with many writers of his day, such as Walter Lippman and Reinhold Niebuhr, he believed only an elite group of responsible and successful individuals should provide the philosophies that would guide the American culture. The economic class, particularly the capitalists, those who kept the economy buzzing, should certainly be part of the elite. Because he was so impressed with propaganda as an agent of stability, he proposed a position be created in various capacities in businesses that would protect the businesses and keep the destructive tendencies of malcontents in check. Since the word “propaganda” began to have a pejorative connotation after the war, he decided the position should be known as Counsel of Public Relations.51 Following the publication of his book, Bernays gained professional fame by using the psychological theories of his uncle to market products or ideas. He did not invent simple PR tactics such as framing or spinning. Ivy Ledbetter Lee, working for John D. Rockefeller is known for framing the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado.52 P.T. Barnum was quite well known for spinning a yarn.53 Bernays persuaded women to smoke in public and persuaded Americans to make bacon a part of the American breakfast.54 He persuaded companies not to advertise by emphasizing utility, but to emphasize desire. A product is not useful, per se, as much as having it will make one’s life so much better. The product is something to be desired, regardless of its usefulness. That PR tactic shaped American advertising throughout the 20th century. Over the years the American public became primed to accept advertising everywhere. Advertising has been in the background of our lives consistently and pervasively. It is extraordinary to think people watch the Super Bowls for the commercials. Yet that is the reality of the fantasy of the American dream broadcast on American televisions well past 1976. In 1976, despite the poor economic circumstances that drained optimism from American life, the capitalist propaganda, there in every commercial break, reassured us there was no other way of looking at life. At the end of Network, as Howard Beale lay dying on stage, commercials comfort and reassure us. Despite death, the selling goes on.

Leaving ‘76

There are two primary influences that led to the creation of Fox News. The first is the creation of Fox’s rival, CNN, and the second is the FCC’s removal of The Fairness Doctrine in 1987, which led to the rise of Talk Radio. CNN was founded in 1980 by Ted Turner. It was the first 24-hour cable channel devoted entirely to news. It made its mark as the premiere international news channel when it broadcasted live from Baghdad during the First Gulf War in 1991.55On the one hand the creation of a new avenue to receive news was encouraging. Broadcast network television had existed on its own for several decades and had come to look the same and broadcast the same stories. Furthermore, being cable, CNN was not subject to FCC regulations as it was not broadcast on the restricted airwaves. On the other hand, the newsroom had to fill the 24/7 format with content. That led to extended conversations between pundits and a veer away from typical newsroom objectivity one would see on the network newscasts, toward more analysis. Nevertheless, CNN was known for its objective stance on the news, and being international, tended to take a more global perspective on events.

In Herman and Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent, the authors raised alarm about the centralization of American media. They noticed in 1983 fifty corporations had dominated the media. By 1990 the number was down to 23. They argued that fewer corporate owners meant less variation in national news coverage, which meant a greater likelihood of propaganda created to control the national narrative.56

The removal of the Fairness Doctrine meant individual broadcast stations, primarily radio at the time, could create programming with specific opinions and were not required to present opposing arguments. This action opened the door for conservative voices, like those of Rush Limbaugh, to begin an explosion of popular Talk Radio formats. The shows tended to be successful, which inferred there was an untapped demographic potential that was being underserved. Roger Ailes, who served as an aide in Richard Nixon’s Whitehouse had long worked to create a conservative news channel. Following CNN’s success, and seeing the massive popularity of conservative Talk Radio, Ailes met with international news publisher, Rupert Murdoch, and they created the Fox News Channel and began supporting Republican causes since 1996, during the Clinton presidency.

Fox immediately gained traction with conservative viewers, and as a marketing tactic, referred to their competition as the Clinton News Network. They actively supported George W. Bush’s efforts and predictably were critical of Barack Obama. By this time their opinion programming in prime time grew shrill and their style became overtly more entertaining as their ratings grew. After Donald Trump was elected in 2016, the prime- time line-up of Laura Ingraham, Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson became cheerleaders for everything Donald Trump represented.

Donald Trump, hot off his reality show, The Apprentice, had become president and reality shows had become news and news had become reality shows and the anger of folks all across America was being reflected back to them from established and respected anchors. The disinformation and conspiracy theories the prime-time opinion line-up would promote were taken as truth by a population that either did not know there is a difference between opinion and news, or just did not care.

Following the election of 2016 and the days leading into impeachment of the President, much has been revealed about Russian meddling in the election and the use of Russian propaganda. Many studies have centered on asking why and how voters could have been manipulated so easily. If Trump’s presidency has proven disruptive to our current political normality, his use of the term “fake news,” has also transformed its meaning into an ideograph, representing all that is detrimental to a free press in contemporary political discourse.57 The fact that <fake news> is used by Trump to describe the mainstream press with whom he disagrees— and by the mainstream press, who point out the President’s use of disinformation—would seem to indicate a circular pattern of logic designed to confuse and manipulate the electorate and to undercut the authority of the free press. At least in terms of propaganda, that is precisely what a Russian author claims is being attempted in the U.S., following its success in post-Soviet Russia. In his book, This is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality, Peter Pomerantsev, describes this technique thusly:

"What was different about these new Russian politicians is that they just didn’t play this factuality game at all. They didn’t care about facts and didn’t pretend to care. So you couldn’t really call out their lies because they were never playing that game. And this is exactly what you see Trump doing right now." 58

Why Trump is using Russian propaganda techniques on the American electorate is a question for another time. The relevant point is that although lying is a traditional behavior for politicians, this new technologically saturated world has altered the game, “The information space, thanks to digital technology, seems more out of control than ever.”59Nevertheless, the legitimate American press is ethically obligated to seek out the truth and report it, all the while fighting their corporate masters or dueling with the public relations reps government authorities place between themselves and the people. Power is everywhere.

Endnotes

-

All the President’s Men, Directed by Alan J. Pakula, 1976, Provo UT: Wildwood Enterprises.

-

Network, Directed by Sidney Lumet, 1976, Los Angeles: MGM.

-

Pauline Kael, “Hot Air,” The New Yorker, (New York: Conde Nast, December 6, 1976).

-

Victor Garcia, “Hannity: Deep State In Full Panic Mode,” Fox News, May 28, 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/hannity-deep-state-in-full-panic-mode

-

Jack Sellers, “Trump, Infowars, Breitbart and the Emergent Propaganda State.” Clarion Ledger, June 1, 2018, https://www.clarionledger.com/story/opinion/columnists/2018/06/01/trump-infowars-breitbart-and-emergent-propaganda-state/663337002/

-

Academy Awards, “Awards Databases,” Oscars.org, Accessed November 23, 2019, https://www.oscars.org/oscars/awards-databases-0

-

Roger Ebert, “All the President’s Men,” Roger Ebert.Com, January 1, 1976, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/all-the-presidents-men-1976

-

Academy Awards, Production Design.

-

Andy Wright, “How ‘All the President’s Men’ Defined the Look of Journalism on Film,” Atlas Obscura, September 29, 2016. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-all-the-presidents-men-defined-the-look-of-journalism-on-screen

-

All the President’s Men.

-

Jonathan Kirshner, Hollywood’s Last Golden Age, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 157.

-

Kirshner, Hollywood, 157.

-

All the President’s Men.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

-

Nicholas Barber, “The Outrageous 40-year-old Film That Predicted the Future,” BBC,November, 30, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20161125-network-at-40-the-film-that-predicted-the-future.

-

Shannon Bowen, “Is PR ethical? Only When Its Practitioners Are,” PR Week, June 24, 2016, https://www.prweek.com/article/1400160/pr-ethical-when-its-practitioners.

- Ibid.

-

Kael,

- Ibid.

-

Dave Itzkoff, Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014), 102.

-

Kael,

-

Sidney Lumet, Making Movies, (New York: Vintage, 1995), 158.

- Ibid.

-

Kirshner, Hollywood, 205.

-

All the President’s Men.

-

Stephen L. Vaughn, Encyclopedia of American Journalism, (New York: Routledge, 2008), 608.

-

SPJ, “SPJ Code of Ethics,” Society of Professional Journalists, 2014, https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

-

All the President’s Men.

-

All the President’s Men.

-

Nicole Hemmer, “The Difference Between Nixon and Trump is Fox News,” Vox, October 17, 2019, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/10/7/20899169/geraldo-rivera-sean-hannity-fox-watergate-trump-nixon-conspiracy-theories.

-

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge, (London: Penguin, 1998), 64.

-

Paul Rabinow, ed., The Foucault Reader: An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought, (London: Penguin, 1991), 194.

-

W. Lance Bennett, News, The Politics of Illusion, Tenth Edition, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 164.

-

Sean Illing, “How Fox News Evolved Into A Propaganda Operation,” Vox, March 22, 2019. https://www.vox.com/2019/3/22/18275835/fox-news-trump-propaganda-tom-rosenstiel

-

Nancy Buirski, “By Sidney Lumet,” PBS, 2015.

-

Paddy Chayefsky, The Imposter, The New York Times, 1968. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/05/22/movies/chayefsky-archives.html#document/p2/a21520.

-

Kirshner, Hollywood, 205.

-

Oliver Darcy, “Mike Bloomberg to Bloomberg News reporters upset over not being able to probe Democrats: 'With your paycheck comes some restrictions,’” CNN, December 6, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/06/media/michael-bloomberg-reporters-investigate-democrats/index.html

-

Tom Griffith, Plato: The Republic. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

-

James Axtell, “Historical Rivalry,” Colonial Williamsburg, Winter, 2007. https://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Winter07/plymouth.cfm.

-

Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004).

-

William E. Gienapp, ‘”Politics Seem to Enter into Everything’: Political Culture in the North, 1840-1860,” in Essays on Antebellum Politics, 1840-1860, ed. Gienapp, et al. (College Station, Tex: Texas A & M University Press, 1982), 41.

-

Richard R. John, “Proprietary Interest: Merchants, Journalists and Antimonopoly in the 1880s,” in Media Nation, ed. Bruce Schulman and Julian Zelizer, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017) 10.

-

Fred J. Cook, The Muckrakers: Crusading Journalists who Changed America. (Garden City, New York: Doubleday,1972), 131.

-

Vaughn, Journalism, 608.

-

Garth Jewett and Victoria O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion, (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2015) 114.

-

Edward Bernays, Propaganda, (New York: IG Publishing, 1928).

-

Bernays, Propaganda, 37.

-

Robert L. Heath, ed. Encyclopedia of Public Relations, (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2005), 482-486.

-

Joanne Wadsworth, “P.T. Barnum: How ‘The Greatest Showman’ Would Survive in PR Today,” Platform Magazine, April 25, 2018. http://platformmagazine.org/2018/04/26/p-t-barnum-how-the-greatest-showman-would-survive-in-pr-today/

-

Tim Adams, "How Freud got under our skin," The Guardian March 10, 2002,https://www.theguardian.com/education/2002/mar/10/medicalscience.highereducation

-

Steve Barkin, American Television News: The Media Marketplace and the Public Interest. (London: Routledge, 2002).

-

Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent, (New York: Pantheon, 1988,2002).

-

Michael C. McGee, “The ‘ideograph’: A link between rhetoric and ideology,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, 66, 1-16. 1980.

-

Sean Illing, “How Fake News Conquered the World,” Vox, October 24, 2019, https://www.vox.com/world/2019/10/24/20908223/trump-russia-fake-news-propaganda-peter-pomerantsev

-

Illing, Fake News.